Annie Ashmore

I am a third year biology major and human rights minor from the Bay Area. I have been studying and lobbying for diverse human rights since 9th grade, and working with different human rights initiatives has given me a passion and a drive to continue fighting.

Casey Crumrine

I am a second year undergraduate from Vusalia, California, studying International Relations at UC Davis. I have alwasys had a passion ofr human rights, but aftertaking Watenpaugh’s class, I realized that I wanted to take that passion and implemebt it inot my carreer choice. Previously being declared under the World Trade and Development track in the International Relatins major. I am now declared under the Peace and Sucrity track, with hopes of being able to pursue a career focuse on making a change in the daily lives of people around the world.

Mason Shmidt

I am a third year from oakdale, California, who is majoring in International Relations at UC Davis. I have been particulary involved and devoted to human rights regarding LGBTQ issues during my time at UC Davis. I have served on the Gender and Sexuality Commision, part of the UC Davis student government, and visited Croatia this past summer to conduct independent research on Queer Politics in Southeast Europe. A lot of my knowledge and passion for human rights has been rootin in a class I took my sophomore year, taught by Dr. Watenpaugh, the head of the Human Rights Department.

Katie Watanabe

I am a third year from Sacramento, California, double majoring in International relations and Japanese. I have long been interested in human rights, and after taking Dr. Watenpaugh’s class on the history of human rights; I was inspired to learn more about the subject. Having spent the summer working at a children’s home (similar to an orphanage) in Japan, I am now interested in studying the Japanese legal system as it relates to children, the judicial system, and human rights, as well as considering a career in social work.

THE PROBLEM OF DISPLACEMENT: INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN UGANDA

Abstract

Methodology

Background

Government’s Neglect of Human Rights Responsibilities

Lack of Upward Mobility in Refugee Camps

Options for Justice

Resources

Abstract

The civil war of Uganda – beginning in 1987 – internally displaced 1.6 million residents of the northern part of the country. Some of those citizens now reside in the Acholi Refugee Quarters in southern Uganda, where they lack basic human rights; these include proper amenities, housing, healthcare, and education. The government’s ambivalence to aid these IDPs (internally displaced persons) entrenches them in this position, and provides little opportunity for upward mobility and the chance to return back to their homeland. They are left in a vicious cycle of poverty due to lack of access to regular food, sanitation, education, and employment opportunities. This research explores the specific human rights violations that are transpiring, drawing from pinnacle sources such as the Makerere University Law School. This report uses an archival overview and analyzes ways in which these human rights issues can be addressed from abroad, whether through exposure campaigning and fundraising, the sending of international relief workers, or other aid options. If successful, these policies might prove applicable to the struggles of the 20 million-plus IDPs around the world in order to help them to return to their homeland.

Background

The region of Northern Uganda was engaged in a brutal civil war from the early 1980s to the mid 2000s. Two insurgent groups, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) rebelled against Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and the military. Their reasons for rebelling included claims of government tribalism against the Acholi Tribe as well as other forms of government corruption, especially within the military. In an attempt to gain control, these two rebel groups abducted thousands of children to serve as a soldiers and fighters.

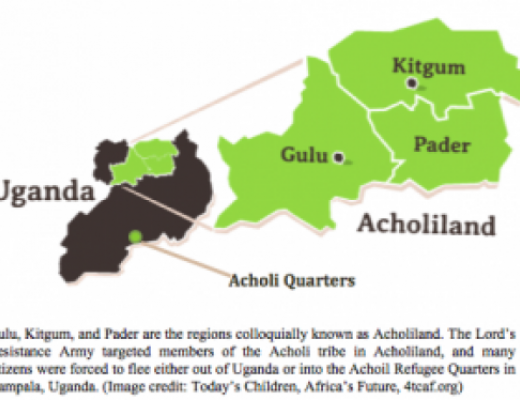

However, the LRA proved to be the most bellicose. In 1998 and 1999, infamous bombings transpired at multiple restaurant and tourist areas in Kampala, representing the ferocity and radicalism of these two groups. The main victims of the LRA had been members of the Acholi Tribe in northern Uganda; interestingly enough, the LRA made claims that they were protecting the Acholi people because the government of Uganda implemented prejudiced policies against the community. Due to the frenetic nature of the civil war, the Acholi people among others were encouraged to move into protective camps known officially as “protected villages” in Southern Uganda. Unfortunately, little preparation was made for them in these villages and they were given little time to displace. In effect, hunger became pervasive, education became practically nonexistent, and their living conditions became squalid and scanty. At its peak, at least two million Ugandans were forcibly displaced, fleeing to places like Masindi, Jinja, Entebbe, or the “Acholi Quarters” in Kampala (Refugee Law Project).

Violence remained prevalent in Northern Uganda for a period of years, which prevented these fleeing individuals from returning to their place of origin. In 2002, 48 people were slaughtered by the LRA. This tragedy received heightened media coverage. In 2003, Sudan allied with Uganda, making ADF essentially an ineffective threat to the Ugandan government and pressured the LRA to declare a cease-fire. However, the LRA was contained to northern Uganda, the area where many internally displaced persons (IDP) sought to return to.

In 2004, Uganda implemented a national policy for IDPs called the Peace, Recovery, and Development Plan for Northern Uganda. Although in concept this was a proper move, its execution was marred by protracted delays. In comparison, 2006 and 2007 were full of various peace talks between the government of Uganda and the LRA. This marked the first wave of IDPs returning to their places of origin. However, both the Ugandan government and the LRA failed to abide by predetermined conditions of their peace talks at various points in time. As a last resort, the Ugandan government launched the 2008 Operation Lightning Thunder, a military strike that pushed the LRA into the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and certain areas of Sudan (Global Security). While this weakened the LRA and some IDPs returned to their places of origin, many returnees faced continued difficulties due to the inadequacy of basic services such as education and government support.

The hardships of the IDPs in their “protected villages” expanded beyond simply lacking physical resources and experiencing violence. Natural disasters over the course of the early 2000s proved to also be a cause of distress. Because these villages lacked proper resources in the first place, many individuals had to shift their residence to as close to the Nile River as possible. Heightened rainfall and depleted foliage due to deforestation wielded a drastic effect on the livelihood of the displaced people. The history and nature of the terrain thus made farming difficult and the formation of infrastructure arduous (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre).

In the end, the long Civil War of Uganda created an internal dilemma that was dealt with improperly and with scarce planning. As a result, many people were forcibly displaced to decrepit living conditions and a number still remain to this day. Human rights violations have been and are currently taking place in many forms and deprive these individuals of accessibility to upward mobility.

Government’s Neglect of Human Rights Responsibilities

Despite the great strides the Ugandan government has made in returning rural IDPs to their homelands, the plight of urban IDP settlements has been largely ignored. As it stands, the remaining IDP clusters are located in the slums of large urban areas, and suffer from a distinct lack of adequate health services, water, food, and sanitation (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2014). Although public health services are ostensibly free for Ugandan citizens, the IDPs in the slums face numerous hidden charges, shortages of medicine that fuel illicit bidding wars, and ploys from profit-seeking health officials. The Acholi Quarters, located in the slums of Kampala and where many of the 95% of Acholi people settled after being forcibly removed from their homes in Northern Uganda, exemplify the struggles that come with the government not providing adequate services. There is inadequate housing for all of the IDPs, as well as fear of forced evictions, as the government has been demolishing homes at the request of neighboring communities who want to see the refugees gone (Mallet, 2010). Sickness levels are high, as the poor housing and sanitation easily facilitate the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera. These living conditions are a far cry from the right to an individual for a standard of living that provides him/her adequate access to health services, food, and housing promised in the UDHR (Article 25). When the UN Refugee Agency concluded its assistance to the Ugandan IDPs in 2012, it did so on the condition that the Ugandan government would step in to ensure the protection of IDPs’ human rights (Spindler, 2012), which it has failed to do.

One potential reason why support for the urban IDPs has been so scarce is that they are not afforded the opportunity to identify or receive aid as Internally Displaced Persons. Urban-based IDPs are perceived by government officials and humanitarian aid groups as being less deserving of assistance, or merely economic migrants as opposed to refugees–allegations that are very clearly false (Refugee Law Project, 2008). Although Uganda’s National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons calls for “local governments to issue to IDPs all necessary documents to enable them to realize full enjoyment of exercise of their rights” (Uganda Office of the Prime Minister, 2004), the government is unwilling to provide such documentation out of fear of overburdening public services and being forced to provide more aid than it can manage (Refugee Law Project, 2010). As such, urban IDPs remain unable to make use of existing structures that assist in post-conflict reconstruction and resettlement, or receive any form of aid for their poor living conditions.

Finally, the Ugandan government has failed to provide adequate support to resettlement efforts by urban IDPs. Once again, the promises in the National Policy on Internally Displaced Persons are seen as not applying to urban IDPs, as opposed to those in rural camps. Chapter 3.14 of the policy states that resettlement kits and resources will be provided to the IDPs after lengthy consideration of input and advice from the IDPs themselves (Ugandan Office of the Prime Minister, 2004). Although dialogue was opened on the possibility of moving urban IDPs back to their homelands, the Office of the Prime Minister requested that the project be shelved (Refugee Law Project 2008), bringing into question the government’s commitment to resettling urban IDPS. Moving back to Northern Uganda would involve multiple trips back and forth, money, supplies to begin farming, etc., provisions the government has hitherto been unwilling to provide.

Lack of Social Upward Mobility in Refugee Camps

The desperate situation of the IDP’s that inhabit the country of Uganda began with the revolution of the Lords’ Resistance Army. Although the initial violence took place years ago, this barbarous army was the origin of many obstacles that continue to set back the recovery of the refugees. The inhumane, savage invasions of the Lords’ Resistance Army influenced the loss of land and essential resources by the refugees in past years. The brutality of the Lords’ Resistance Army prevented refugees from accessing the provisions provided to them. Because the fear that stemmed from invasions of refugee camps, the refugees did not utilize the delivery of vital provisions and humanitarian assistance that was provided to them. For example, the “fear of the LRA [stopped] people from farming”, which was “the economic mainstay of livelihoods in [that] area” (Deng). This initial loss of vital provisions and humanitarian assistance is what initiated the desperate situation and level of poverty experienced by the IDPs of Uganda still today.

This is an issue because “food stocks are scarce, water supply is severely inefficient, sanitation is poor, and the provision of health and education services is minimal” in the refugee camps of Uganda. Because of the initial inability of the refugees to obtain resources necessary for farming, a majority do not farm at all, and the ones who did rarely produced enough for themselves. This began the increase in poverty that is still experienced in the urban camps that the IDPs inhabit today. Paired with the complexity of the legal land system in Uganda, this produced an environment where being prosperous was almost impossible. Because a majority of the land that the refugees once lived on is customary tenure – land owned by a community – there is no recognizing documents of ownerships to be accepted by the state during disputes. Even if refugees could fight this, they cannot afford to pay the legal fees associated with settling these disputes because they never obtained the resources to become a prosper community (Internal Displacement).

This level of poverty was a key cause for the inefficient access to services such as healthcare and education, and led to the physically and mentally debilitating conditions of the refugees. It also interfered with the ability of children to attend school, as although the government offers free primary and secondary schooling, the hidden costs associated with receiving an education prevents children from going to school. Children have to work to contribute to their household incomes, which often becomes a priority above education. The matter of having to travel to go to school is an issue as well, as there have been 30,000 abductions of children in recent years who were forced to serve as soldiers, porters, or sex slaves. It becomes an easier and safer option to remain in the camps and to work, interfering with the opportunity for education (Internal Displacement).

Because of the lack of government involvement, it is difficult for there to be any upward mobility within the refugee camps of Uganda. Uganda is ranked 130th out of 175 on the Transparency International corruptions perception index, and the conditions will most likely continue to get worse because of the UN’s decision to pull out of the UNHCR (Internal & Spindler). With the loss of land and constant fear, the refugees might never obtain the resources necessary to their revival.

Options for Justice

Justice for the displaced Acholis is complex to define, and it requires a multifaceted approach. In addition to basic human rights like improved living conditions, education, and healthcare, the Acholi feel understandably marginalized by the Ugandan government. Although community based and international aid has the potential to do a lot of good, we recommend the government be held responsible for coordinating at least some of these efforts. If the government refuses to view the Acholi Quarters as a serious problem that requires their attention, there is a high risk of social unrest resulting from the lack of communication and peace building (IDMC 7).

In the past, the government has only exacerbated problems in the Acholi Quarters due to corruption and their disorganized, undisciplined army (Human Rights Watch 1). Although the government has a reputation for a lackadaisical approach towards the suffering in the Acholi Quarters, including the government as a part of the solution would promote peace and healing between the northern and southern regions of Uganda as well as between the Acholis and the government. However, due to its track record, the government’s involvement and transparency in its efforts should be audited by national organizations, like the Refugee Law Project, in order to minimize corruption. The government’s involvement could potentially entail creating solely government-based solutions, like working to provide national IDs to IDPs—as it promised in the national IDP policy (Resettlement Assistance 2)—, providing tax breaks to people who work at IDP development projects, and allowing the International Criminal Court to investigate the situation without further obstruction (Human Rights Watch 1).

In addition to support from the government, local social service projects have the potential to develop the Acholi Quarters by providing options for sustainability and possible rehoming opportunities. Native Ugandans are familiar with the suffering in the Quarters and have the leadership capabilities to mobilize and create projects. These projects could take the form of providing counseling, job training, and other social services. However, because the issues are emotionally charged—involving complicated tribalism, marginalization, and delays to rebuilding—there is also potential for biased decision making and corruption within the local projects (Gov’t Stalls 2). If local visions for projects are funded through outside funds, like the government or international humanitarian organizations, we recommend that they be required to increase transparency, which will allow local projects to thrive without Western influence or corruption.

International aid organizations can also provide social service options, but ultimately the local problems should be solved with local solutions for the reasons stated above (Human Rights Watch 4). Funds and awareness from the international community can be useful if they are channeled into locally run projects. In addition to funding, international organizations can be used to put pressure on the Ugandan government for increased transparency and aid to the Acholi Quarters (IDMC 9). In general, the government is invested in maintaining its image and has been responsive in the past to recommendations from organizations. International funds, as well as calls for transparency and accountability will be the glue that holds government assistance and local social service projects together. This combination will foster a culture of unbiased, efficient, effective, and empowering aid.

Works Cited

Deng, Francis M. “Internally Displaced Persons Uganda–A Forgotten Crisis.” The Brookings-SAIS Institute on Internal Displacement.58:19. Print.

Human Rights Watch. Uprooted and Forgotten: Impunity and Human Rights Abuses in Northern Uganda. © 2005 by Human Rights Watch.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. New Displacement in Uganda Continues Alongside Long-Term Recovery Needs. © 2014 by Internal Displacement Monitoring Center.

Mallett, Richard. “Transition, Connection and Uncertainty: IDPs in Kampala.”Forced Migration Review (2010): n. pag. Forced Migration Review. Feb. 2010. Web. 20 Feb. 2015.

No Author. “Gov’t Stalls Urban IDP Profiling.” Refugee Law Project (2008): n. pag. Refugee Law Project. Makerere University, Oct. 2010. Web. 31 Jan. 2015.

No Author. “Resettlement Assistance Too Little, Urban IDPs Say.” Refugee Law Project (2008): n. pag. Refugee Law Project. Makerere University, Jul. 2008. Web. 31 Jan. 2015.

No Author. “Uganda Civil War.” GlobalSecurity.org. 27 January 2012. Web. 10 March 2015.

No Author. “Uganda’s Urban IDPs Risk Being Left Out Of Government’s Return Plans.” Refugee Law Project (2008): n. pag. Refugee Law Project. Makerere University, Mar. 2008. Web. 31 Jan. 2015.

Spindler, William. UNHCR Closes Chapter on Internally Displaced Persons in Uganda.UNCHR, 6 January 2012.Web. 7 March 2015.

Uganda Office of the Prime Minister and Department of Disaster Preparedness and Refugees. The National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons. The Republic of Uganda: 2004. Print.