I graduated from UC Davis in June 2015. I completed an individual major in Law, Government, and Ethics with a minor in Latin American and Hemispheric Studies. I am currently applying for the Fulbright Garcia-Robles research grant to conduct historical research on the use of force in Mexico. I have always had a passion for the different cultures of Latin America, and because of this, became concerned about the human rights violations and abuses that have occurred in some of these countries. I believe it is important to discuss and share what experiences people have had when their rights are violated in order to promote memory and tolerance, but most of all, to prevent these violations from happening again.

http://www.50jpg.ch/archives/2010/files/gimgs/34_v-p-sv-e-00172h.jpg

“AN INTERVIEW WITH GUSTAVO MIRANDA” BY EMILY BRUCE

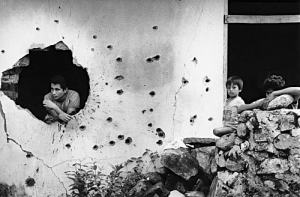

The following is a narrative of an interview with Gustavo Miranda, a custodian at UC Davis. Gustavo’s story exemplifies human rights in that it provides a testament to his experiences during the civil war in El Salvador. This narrative helps one understand human rights in that it starts with listening. In order to promote and protect these rights, we first must learn how to listen and build a connection with others. I walked down the long fluorescent-lit hallways of Tupper Hall. Besides the presence of my friend Faustin, the atmosphere was deserted and still. Almost sterile. His loosely fitted custodial shirt swayed with his walking. He talked to me about how great it was that I decided to interview his co-worker. “My friend Gustavo is from El Salvador. He is a very nice man,” said Faustin, as he led me down each corridor. “Gustavo!” he finally called as he approached a smaller, darkened hallway that was off to the side. “Here is my friend Emily to interview you!” I saw a custodian’s cart emerge first, a bin to collect trash, a mop, and a “Caution: Floor Wet” sign. After a moment of waiting, my interviewee emerged from the darkened hall. He was short in stature, had a stocky build, and graying hair in a crew cut style. I noticed a faded tear drop tattoo on the lower left corner of his eye. Gustavo smiled and shook my hand. His grip was firm and clammy. “Okay, I will leave it up to you guys now. Thank you, Gustavo,” stated Faustin, as he quickly walked away to return to his work. Gustavo and I made small talk as he directed me to a conference room just down the hall. “Wow! So you’re from El Salvador?” I said as we entered the room. “Yes, I am,” he said, laughing lightly. Gustavo Miranda grew up in San Salvador, the capitol of El Salvador, until he left for the United States in 1983. He reminisced of his childhood telling me of his experiences working with his father’s molino (mill) business. His family had machines at their house where people would come to make their tortillas. The customers would use the machinery in the process and pay the Miranda family money for their resources. While his father manned the business at home, Gustavo’s mother worked at an abarrote (convenience store). Hearing about the tenacity and generosity that went into his parents’ work helped me understand where Gustavo got his qualities. “My father was always giving out food, giving water to someone working on the street,” he stated, “always helping people.” Gustavo’s father had a kind heart, making him very well-known in the community which reflected upon his family as well. Gustavo’s father was an extremely hardworking man who employed the help of his family to make their lives successful in the community. My surprise sparked humor in Gustavo when I asked him if he had ever helped his father with their business. “We never had time to go out and play football,” he laughed “I was always with my father, working.” Gustavo described the people of El Salvador back then as being poor but happy. When he was growing up, the country was using the currency of colones, but it later switched to US dollars in the year 2001, which heavily impacted the poor communities. Now, people’s lives are increasingly stressful, causing them to work more in order to earn more income. Gustavo mentioned that when he was growing up, people were poor, but a person could at least put food on the table. Today, families are making five dollars a week, and sometimes they are not able to have dinner that night. Although I felt a hint of nostalgia during some moments when talking with Gustavo, he was very adamant about never returning to El Salvador. This insistency was not only the result of the lack of opportunity in his home country but was also a response to the violence that he endured while living there. I could tell during our interview that Gustavo was more vocal about his experiences in El Salvador than he was about his life here in the United States. Gustavo grew up near a volcano in the neighborhood of Colonia Escalon. He was able to see the fighting on the peak of the mountain from his house. This mountain was the base camp for the guerrilla troops who were fighting against the Salvadoran government during the Civil War of the 1980s. One day, Gustavo saw government helicopters circling a group of guerrillas on the mountain top. The flames burned the guerrillas alive. Gustavo stated simply “it was very dramatic.” He spoke of these experiences very pragmatically. When he would walk through the streets of San Salvador, even on his way to school, he would pass by numerous bodies that littered the streets. One included a presidential candidate who was taken from his home and executed with a bullet in the head. Gustavo expressed his confusion stating that the man still had his watch and his rings on. They did not steal anything from him. One evening, when Gustavo was about fifteen or sixteen years old, he was taken from his home and thrown into the street by the guerrillas. Gustavo remembered the guerrilla commander’s statement: “Okay Gustavo, you want to come with us? We’re going to kill you.” Gustavo told me that all he could think about was praying. He felt a sense of incredible hope and strength and addressed the guerrilla commander: “If you’re going to kill me, kill me right here. Don’t kill me in another place and leave my pieces on the ground... Kill me right here.” As Gustavo relived this story, I noticed his legs bouncing up and down with nervous energy as his arms and hands rested undisturbed on top of the conference table. He was so close to being executed that he recalled feeling “the blood on my mouth... like everything is coming because they want to kill you in that moment, with the machete near to you.” Fortunately, Gustavo was saved by his brother who persuaded the guerrillas to leave him alone. However, he would continue to experience these incidences-- if not to himself, then to his other family members. What caught me off guard was when Gustavo laughed, and told me that these occurrences were “like a movie.” I realized that this was his way of bridging this gap of understanding between us. Gustavo is a calm man with a warm smile that shines through his tough, reformed appearance. His undying faith, bravery, and openness are characteristic of what he endured while living in El Salvador. As I sat across the table from Gustavo, I reflected upon all that he had told me. His willingness to recount his story made me realize the importance of listening and sharing experiences with others in order to build a connection between our differences. When our interview had finished, I couldn’t help but think that he would be returning to his work, quietly cleaning the corridors of Tupper Hall.