I am a third year student majoring in science and technology studies. I work as an undergraduate research assistant studying the effects of the lactoferrin receptor in intestinal diseases. I have always been very passionate about human rights, which led me to take on this project. My colleagues and I wrote this piece to raise awareness of racial prejudice, which unfortunately is still prevalent today. Our hope is that it will spark conversation and provide new perspectives.

nytimes.com

LIBERTY & JUSTICE FOR ALL? THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF RACIALLY DRIVEN MOB VIOLENCE

Abstract

Background: A Violent History

Current Issues: Contemporary Racist Violence

Call to Action: Healing and Moving Forward Through Memorialization

Strategies and Conflicts: Roadblocks and Obstacles to Commemoration

Concluding Remarks

Abstract

In this paper, we argue that the commemoration of past human rights offences is not only necessary for remembering lives lost, but necessary for fostering a political response. Recently, record of 700 additional lynchings in the Southern United States between 1877 and 1950 were unearthed. This brings the total to more than 4,000 African American people killed in this 73-year period. Remembrance of these lynchings is particularly relevant, considering current racial conflicts; it also invites a conversation regarding terrorism in the US. Memorials creating an idea of shared mourning have been used around the world for many years, in the wake of tragedies ranging from war to disappearances under dictatorships. Memorializing these recently rediscovered lynchings would further push a critical social conversation into national light subsequent to the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and several other black Americans. In this paper, we will urge the United States National Parks Service to work with state and local arts commissions to develop a systematic memorialization process while inviting a conversation of polarized opinion. We will use examples of past memorials in and outside of the United States and discuss the ways in which memorials serve not only as a way to commemorate lives lost, but also as a vehicle to stimulate discussion and understanding as humanity faces similar issues today.

A Violent History

The period between the conclusion of the Civil War and the end of World War II was one of extreme terror and violence in much of the southern United States. Driven by a desire to maintain the institutionalized hierarchy between blacks and whites disrupted by Reconstruction, lynching of African Americans by white Southerners became a relatively common, accepted occurrence. Lynching, as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, means “To condemn and punish by lynch law. In early use, implying chiefly the infliction of punishment such as whipping, tarring and feathering, or the like; now only, to inflict sentence of death by lynch law.”[1] Lynchings created “a climate of terror” and this institutionalized violence was used as “a weapon for maintaining some degree of control over the African-American labor force.”[2]

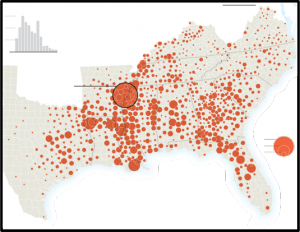

The below map shows concentration of “premeditated murders carried out by at least three people from 1877 to 1950 in 12 Southern states.”[3] Those who took part and supported these violent practices justified their actions by citing African Americans’ supposed inferiority “by reason of [their] race.”[4] Because of this theoretical inferiority, and because “many whites believed blacks too animalistic for the courts to control,” lynching was seen as an appropriate alternative to normal court proceedings.[5] African Americans were assumed to be criminal by nature, and reasons behind lynchings (irrespective of actual guilt, and regardless of any evidence) could range from “murder… felonious assault… rape… theft…” to “frightening school children … trying to act like a white man” to “seeking employment in restaurant … boastful remarks.”[6] Indeed, a letter printed in the New York Times by a white Georgia native explains:

The reason the negroes are generally the victims of lynch law is because the negro is generally the criminal. … [Rape] is almost always committed by negroes, and negroes of the lowest order… when it is committed the utmost care is taken to identify the criminal and only when his identity is beyond question is the execution ordered. It is done in a quiet, decided way as a general thing, although in cases of great atrocity sometimes the criminal is shot as well as hanged.[7]

Concentration of mob violence in the South between 1877 and 1950

Any cursory study of lynching in the South during this time knows the above statement detailing the quasi-legal manner in which lynchings were carried out is an open lie. Lynching was far from a “quiet, decided” process; it was rather an exceptionally violent manifestation of racism. Lynchings became public events, with thousands of people, including families with young children in attendance. Indeed, “one lynching in 1916 in Waco, Texas, attracted a crowd of fifteen thousand,” indicating to the perpetrators that their vigilante justice was not only accepted, but encouraged. The lynchers avoided anonymity because they were sure they would never be punished, supported by “the willingness of the crowd to participate in lynching – to cheer, to yell their encouragement, or just to stand and watch without intervention.”[8]

As much as history revisionists might wish to believe it, lynching was not a fringe activity, endorsed only by groups of extremists. In fact, “many lynching photographs show crowds that represent what can best be described as a cross section of the white community.”[9] People from all walks of life – men, women, families, businessmen, politicians – validated this enactment of violent ‘justice’ both tacitly and explicitly. Not only did crowds gather and voice encouragement at public lynchings, but in the relatively rare event that lynchers were called to trial “witnesses called to testify before a grand jury regularly insisted that they recognized no one in the crowd [during the lynching],” acting in solidarity with the lynchers and protecting their identity from prosecutors.[10] Additionally, as Ifill points out, “systematic racial or ethnic violence cannot flourish without the active participation and support of a community’s institutions… the individual actor is emboldened because he believes that his community’s institutions – its legal system, the media, and the business community – will ultimately support or condone his actions”.[11]

Contemporary Racist Violence

While lynching has declined in the Southern states since it was legally banned, it left behind a lasting legacy that “echoed through the latter half of the twentieth century.”[12] African Americans continued to face violence from whites during their efforts to overcome the entrenched social boundaries to which lynching had strongly contributed. The culture of racism also presented a major challenge to the civil rights movement and the criminal justice system, an obstacle that remains unresolved today. The lingering racism caused by racial terror and widespread lynching was so deep-rooted that many white southerners who lived during that time failed to change their beliefs and values long after the era of racial terror ended. During the Civil Rights movement, many white police officers and community members actively opposed black activists by beating, shooting, and bombing them at protests and rallies. The continued violent racism is cause to wonder whether banning lynching changed anything. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “Perhaps the most important reason that lynching declined is that it was replaced by a more palatable form of violence.”[13] By 1915, court-ordered executions exceeded the number of public lynchings in former slave states. Despite being the clear minority in the Southern population, blacks comprised the majority of those sentenced to death, indicating that race remained a key factor in capital sentencing. Between 1910 and 1950, blacks comprised just 22% of the South’s population, yet constituted the 75% of convicts executed in that same time period.[14] “In the 1987 case of McCleskey v. Kemp, the Supreme Court considered statistical evidence demonstrating that Georgia decision makers were more than four times as likely to impose death for the killing of a white person than a black person…”[15] Although lynching was outlawed by the government, the large-scale executions of black people did not cease and instead were conducted legally with the consent of the judges and all-white juries, many of whom were influenced by the culture of racism that the newly-banned practice of lynching had helped build.

The lynching era “significantly marginalized black people in the country’s political, economic, and social systems; and it fueled massive migration of black refugees out of the South.”[16] In addition, it inflicted traumatic psychological wounds on both the black and white communities. The families of lynching victims as well as witnesses to those violations of human rights were left with fear and hatred towards white people. On the other hand, whites who participated in or witnessed the lynchings and raised their children in the culture of racism it thrived under became more inclined to racist beliefs and values. The indifference by state officials to the impact of lynchings also led to unconfronted national and institutional wounds, setting the stage for the racial conflicts and tensions today. Lynching fostered a deep-rooted culture of violence and segregation between races and the animosity it created between blacks and whites caused the outrage that came with incidents of white-on-black violence, such as the Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin shootings.

Healing and Moving Forward Through Memorialization

The first step in confronting and healing these injuries is to memorialize lynching, and thus open a conversation addressing racial tensions in our country. We call upon the National Parks Service to work with state and local arts commissions to develop a systematic process of memorialization. This memorialization will make a political conversation regarding these issues more accessible. Outside of the realm of those physically injured by lynchings, there remain those psychologically affected by such events stemming from racial tension. This type of injury is not dependent on skin color, and persists through generations.

An example of successful memorialization in the South from an earlier period is due to the work of the Equal Justice Initiative, who erected public markers in Alabama about the history of slavery. As seen in the image to the right, these markers each told a story and worked to heal the psychological wounds that still created a rift between communities in the South.[17] In recent times, these wounds have been reopened, in situations where people of every skin color are forced to see racial violence across the country through news reports, or right in front of them.

Lynching was not a crime that occurred in isolated areas of the southern United States. These were targeted terror campaigns known for using racial violence and the perpetuating of the unjust social order.[18] This worked to maintain a culture of “otherness”, a concept that still lives on today.

As Katherine Hite, professor of Political Science at Vassar College said, “suffering must be a public activity.”[19] This does not mean to inflict guilt upon those responsible for the suffering, rather to create an environment in which people are unafraid of publicly expressing their grief. In this public expression, a conversation that may otherwise have been disregarded will be elicited. When groups stand together, with combined knowledge and grief, they can move beyond feelings of helplessness and anger, into a world where through engagement and listening, groups may recover. It is easy for incidents of racial violence to recur when we as a country fail to recognize the causes and roots of modern racism. Past violence paired with modern tension makes this public acknowledgment in the form of commemoration all the more important. It will not only be beneficial for the “victims and survivors, but also for the perpetrators and bystanders who suffer from trauma and damage related to their participation in systematic violence and dehumanization.”[20] Now that an opportunity has been presented to combine both past violence (regarding the newly discovered lynchings) and the current racial situation (Black Lives Matter and related groups), there also lies an invitation to a conversation. This conversation must not be between the same people over and over, but opened up to new audiences through these memorials.

Image: The Equal Justice Initiative and community leaders work together to unveil a public memorial in Alabama in 2013

The discussion proposed through memorialization and less hostile environments is one of multiple origins. It could be related to reparations for the communities that were subject to atrocities dating back to the Civil War, or solely in regards to these specific lynchings, or to the modern Black Lives Matter movement. This public discussion will ameliorate relations, while giving communities a chance to share how they best feel memorialization will heal the wrongs they have faced. Structural poverty, issues within the justice system and familial issues within the African American communities must be not only discussed, but steps taken towards helping and fixing these deep-seated problems. Racial tensions, as noted in the previous two sections, are nothing new to our nation. It is time that our country works together to solve these issues that have plagued generations.

It is imperative that the National Parks Service work with local artists. This would show not only grassroots support, but also national support, and the beginning of an amendment to the wrongs committed by the states. This must not be a solely governmental change, where locals feel stepped on by officials, rather a two-sided agreement, with conversation in between. This memorialization will help build solidarity within the movement for equality, as well as invite groups and individuals into the public sphere to discuss how they best see this occurring, in a manner which recognizes lives lost in the past and present in a respectful manner.

Roadblocks and Obstacles to Commemoration

Today retrospection on lynching evokes particularly salient memories of pain that has been etched into black communities. Commemoration of deaths caused by lynchings throughout the South creates mixed emotions from within communities where this practice took place. Some southern communities have discovered that talking about lynching is an infallible way to surface long simmering contention on racism. Recalling the traumatic history behind lynching in America’s violent past can be challenging for all members to confront, not necessarily because they are opposed to commercialization but because of the differing opinions that surround the issue.[21]

Commemoration of lynching sites invites discussion about this shameful part of history that can either propel communities to pragmatic action by taking steps to memorialize sites, or polarize the members. Some community members would rather maintain a ‘curtain of silence’ about how these events took place and avoid discussion on what occurred in the past.[22] In this way, the relationship among blacks and whites on the human rights issue of lynching remains frozen, and argument for commemoration falls on deaf ears. However to move past barriers against commemoration, the public must first recognize the way in which lynchings have shaped society and be able to have open dialogue among community members about the issue.[23]

One argument against commemorations in the public sphere is that communal areas cannot be a sacred space.[24] Those opposed to commemoration contend that everyday activities would be at odds with the special nature of sites that have particular historical remembrance. Further, recalling these events would not encourage a community to move forward when they are continually reminded of the offenses, and that it would draw greater distinction between blacks and whites. Another argument is that constructing commemoration of historical lynching sites may be so disturbing that community members would rather destroy any signs of former violence, as a way to symbolize that this behavior no longer exists.

Public memorials and markers that honor African Americans, or challenge white supremacy will not be easy to achieve or maintain. Executing this part of a commemoration plan will require confrontation of racists’ and postracial enthusiasts’ opposition to monuments that challenge white supremacy. Today white conservative opposition to monuments and memorials celebrating African Americans or observing moments in their histories is common throughout the South and stands as yet another obstacle to commemoration.[25]

City and state governments in the south are also instigating backlash to commemorations. In cities such as Montgomery, Alabama, public markers for commemoration are not received with the same enthusiasm as the abundance of Civil War and Civil Rights Movement memorials that occupy space in the public forum.[26] Montgomery is just one instance of a major city that does not support commemoration, despite -or perhaps because of – their history particularly embroiled in lynching. Communities that do not recognize markers and memorials as an effort to enhance the diversity of already existing monuments exemplify yet another attitude that must be overcome in order to move forward with our call to action.[27] Addressing the ignored racial terror from the nation’s collective memory is a matter that must be resolved.

Recognizing the extent of damage that lynching has inflicted on American society would mean managing difficult emotions that communities have left buried for generations. Many community members would rather not accept this challenge because American history has typically been associated with feelings of hope, and freedom, and not violence and oppression.

Concluding Remarks

Commemorations are crucial in raising awareness. The commemoration of past human rights offenses is not only necessary for remembering lives lost, but also for fostering a political response. Furthermore, commemorations promote an atmosphere which supports discussion and political conversation. Racial issues should be discussed and not ignored; yet it has become increasingly difficult to discuss racism, as many Americans claim not to see race and cling to the idea of a “colorblind” society. However, if one cannot see racism, then one cannot fix it. Ignoring race doesn’t solve racism, it simply disregards all of the struggles black Americans have faced.

The process of commemoration will “force people to reckon with the narrative through-line of the country’s vicious racial history, rather than thinking of that history in a short-range, piecemeal way.”[28] It is vital to face the truth and realize what racial injustices have taken place. Current research on violence and the justice system promotes “the urgent need to engage in public conversations about racial history that begins a process of truth and reconciliation in this country.”[29] This parallels the current conflict between the Armenians and the Turks. The Armenian people want the Turks to admit to the Armenian genocide, while the Turks refuse to acknowledge that it ever happened. Providing recognition of past wrongs would set the groundwork for reconciliation, which is why commemorations are essential for the country to heal. Only after addressing and discussing the damage caused by lynching, can people begin to truly address the current racial problems that exist today as a result from it. Bryan Stevenson, the director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), asserts “we cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it.”[30] Finally, commemoration also respects people who lost their lives and their loved ones.

One reason that commemorations are absolutely necessary is because lynching shaped what it means to be black in America. Lynchings “reinforced a narrative of racial difference and a legacy of racial inequality that is readily apparent in our criminal justice system today.”[31] Police brutality is not the only issue African Americans face. Other issues such as “mass incarceration, racially biased capital punishment, excessive sentencing, disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were shaped by the terror era.”[32]

In conclusion, lynching occurred as a violent manifestation of racism in the era following the Civil War. It left behind a lasting legacy of racism in America by inflicting traumatic physical and psychological wounds. Lynching constituted a major human rights violation, disregarding the right to life and personal security. Furthermore, it fostered a deep-rooted culture of violence and polarization between races. It also created a lasting animosity between people of different races, which led to current crimes against African Americans, such as Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and many others. Yet, memorialization allows the opportunity to create a welcoming environment in which one can openly share and express their grief. It also invites political conversation by combining past violence with current racial tension. Successful memorialization is possible, as many commemorations remembering black history have already been erected in the south. Engaging local artists to create new memorials will help to recognize the 4,000 people who were lynched during a period of horrific racial terror. The lost lives can never be replaced, but these commemorations can help the nation heal by providing some solace for the families who lost loved ones and welcoming the much-needed opportunity to discuss existing racial issues.

[1] “Lynch.” www.oed.com. Oxford University Press, n.d. Web.

[2] Tolnay, Stewart Emory., and E. M. Beck. A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1995. Print.19

[3] Equal Justice Initiative. “Map of 73 Years of Lynchings.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 09 Feb. 2015. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

[4] Raper, Arthur Franklin. The Tragedy of Lynching. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina, 1933. Print.

[5] Waldrep, Christopher. Lynching in America: A History in Documents. New York: New York UP, 2006. Print.

[6] Raper 36

[7] Waldrep 7

[8] Ifill, Sherrilyn A. On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-first Century. Boston: Beacon, 2007. Print.

[9] Ifill 58

[10] Ifill 51

[11] Ifill 155

[12] Equal Justice Initiative, 19

[13] Equal Justice Initiative, 21

[14] Equal Justice Initiative, 21

[15] Equal Justice Initiative, 21

[16] Equal Justice Initiative, 22

[17] Image found at: ://www.eji.org/files/BAT_2696.jpg

[18] Equal Justice Initiative (“Trauma & Legacy of Lynching”)

[19] Hite, Kathrine. “Politics, Human Rights, and the Art of Commemoration in Latin America.” International House, Davis. 12 Feb. 2015. Lecture.

[20] Equal Justice Initiative

[21] Ifill 20

[22] Chideya, Farai. “Confronting a Legacy of Lynching.” NPR. NPR, 7 Mar. 2007. Web.

[23] Ifill

[24] Autry, La Tanya. “The Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial as Hallowed Ground.” Art Stuff Matters. Web. 8 Mar. 2015.

[25] Robertson, Campbell. “History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 9 Feb. 2015. Web.

[26] Robertson

[27] Williams, Kidada. “What the Black Lynchings Numbers Don’t Reveal.” Dame Magazine. Dame Magazine, 16 Feb. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

[28] New York Times

[29] Equal Justice Initiative

[30] Equal Justice Initiative

[31] Equal Justice Initiative

[32] Equal Justice Initiative